“I’ve always been interested in technology and pictures,” says David Hockney, still sharp at 85 in both mind and style, and preparing to unleash one of his most ambitious projects to date. With Bigger & Closer (not smaller & further away), Hockney joins the likes of Van Gogh, Dalí and Klimt as the subject of an immersive art show. The difference being, of course, that he’s still around to make sure it’s just as he wants it.

Up close and personal

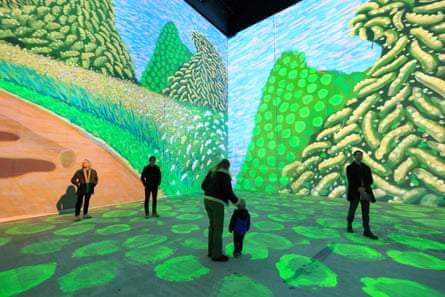

The show takes place at Lightroom, a new venue in London’s Kings Cross. During the hour-long performance, various Hockney works dance around the venue’s walls to a soundtrack composed by Nico Muhly. Occasionally we hear Hockney’s unmistakable Yorkshire accent as he muses on a lifetime in art, offers insights into his techniques and gives visitors the opportunity to experience his unique way of seeing the world.

My art has always been immersive, so I kind of grasped what it involved. You’ve got four walls and a floor – it’s a completely new medium really.”

- Projections (left to right): Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy (1968), American Collectors (Fred and Marcia Weisman, 1968) and (in part) Beverly Hills Housewife (1967).

Around 250 of Hockney’s works are featured, spanning his six-decade career: some well known, others rare, and some drawn specially for the occasion.

Over three years in the making, the show features 1,408 loudspeakers, 28 projectors and a digital canvas size of approximately 108m pixels.

This felt like it was moving something on. So I said, OK, let’s do it!”

‘Nature is an endless subject’

Because much of Hockney’s later work has been made with an iPad, this digital show allows his paintings to unfurl on screen just as he would have created them – with clouds appearing and flowers blooming as the sound of birdsong fills the room. There’s even a digital sunrise.

You can watch the whole drawing being made. It plays back every mark you did. It’s like looking over someone’s shoulder to see them draw, and people always love doing that with an artist, don’t they?

The exhibition is split into several sections, with mini-lessons explaining how only paint can convey the true majesty of the Grand Canyon, or how photographs fail to capture how we really see things. Using examples of his chair paintings or photo collages, Hockney explains how paint can bend the rules of optics and open up the sensation of time in a way photography cannot.

We assume we look the same way as a camera, but we don’t. We’re always moving, or the eyes are always moving. Cameras see geometrically but we see psychologically. If you play with perspective it allows the viewer to wander in and look around

‘Nobody had painted LA before’

- top: Mulholland Drive, June 1986 (1986), left: Nichols Canyon (1980), a colour-treated abstraction of Mulholland Drive created in collaboration with the director for the exhibition

During the show’s commentary Hockney talks about arriving in “sunny and sexy” Los Angeles at the age of 24 and realising that it was twice a good as he’d expected. “I thought, this is the place for me!”. He didn’t know a soul there, but basked in the freedom of the road and the clarity of the light. In particular he was drawn to the fact that nobody had really painted the city before – and so he began painting panoramic landscapes.

Paris has been painted by marvellous painters, and London too. But LA didn’t even have a building that you would recognise. I was attracted to that. It was the first place I’ve actually painted.”

While based in Los Angeles, Hockney was famous for his “Wagner drives”, when he would take friends on a drive through Malibu Canyon, the Santa Monica mountains or the San Gabriel mountains with the German composer as the soundtrack. The trick was to get the timing right, so that the journey peaked in time with the music, just as the sun was setting.

In 2012, Hockney made a movie of these euphoric journeys, fixing tiny cameras to his vehicle to document the views from all angles. With this new show, Hockney could invite everyone along for the ride.

I used to love taking people on it. They’d have to come down to Malibu about an hour before the sun set, whatever time of year it was. And then we’d drive up the coast with West Side Story – ‘I like to be in America!’, things like that. Then when I turned up the hill, it went to the Wagner and people loved it. I mean, even some kids loved it. They would have never listened to Wagner’s Prelude to Parsifal if we hadn’t been moving. But when you have movement and music in a landscape, I think it’s very, very good and interesting.”

Setting the stage

Hockney has designed many stage sets during his career, including multiple operas during the 1980s – which get a prominent showing at the Lightroom exhibition.

The opera stage designs are not that well known, but they’re a real part of my work. So we’ve put them in here, and we’ve been animating things, and they look terrific. In 1987 I did the sets for [Wagner’s 1865 opera] Tristan und Isolde. I thought at the time it felt like you were on a ship … but with this version, you’re really on the ship!”

I can get frustrated that people don’t really look at things closely. But you can’t expect everybody to look at things like I do, because I’m drawing and painting things.”

Was that the motivation behind this show – that people would learn how to see more like him? “I’m just making suggestions to people, really. That’s all I can do. And then they can go home and think about it a bit.”

Eyes on the future

I’m 85 years old, so I don’t know how much longer I have. But some young person might see something here and think, well, I can see what you could do with this. I hope what it will do is give young people some ideas – perhaps on how to make movies in a completely new way. Cinema is dying. You can see any Hollywood film on a big screen at home. But this is a new kind of theatre, a new kind of cinema. With this, you have to go out and see it. And people do like going out!”

You might assume that, well into his ninth decade, this could be Hockney’s last big piece of work. But actually, it’s just given him more ideas.

It’s made me think we might do another opera: Ravel’s L’enfant et les Sortilèges. It’s 45 minutes long, so I think it could be done with this method.” So still hungry to keep working, then? ‘Oh yeah,’ he says. ‘Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes.’”

Bigger & Closer (not smaller & further away) is at Lightroom, London from 22 February until 4 June 2023

More Stories

The Overall Winner of The Architecture Drawing Prize

10 Online Drawing Games To Play With Your Friends

Earth Day Poster Drawing | Top Best 6 Creative Earth Day Poster Design Ideas