When my wife Jan and I arrived in Sussex in 1980, we started riding the South Downs on moonlit nights. The white chalk paths reflected the light and made the going easy, despite the steep drops and our night-wary horses. Once on the crest, you could see the lights of ships coming up the Channel to one side and the villages twinkling down below on the other. It is a magical space and provided a wonderful introduction to Britain, which we had come to from South Africa. As we clip-clopped home along the dark pathways, curtains would twitch – not surprisingly, as the last night riders hereabouts were smugglers transporting French brandy from the coast to London via these deep, hidden lanes.

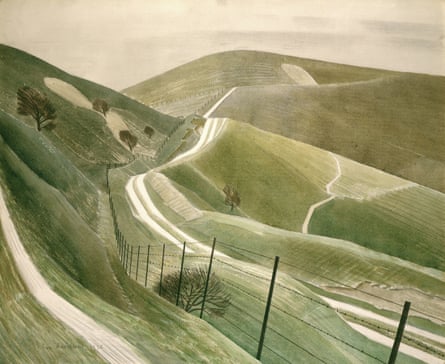

Sussex Landscape: Chalk, Wood and Water, a new exhibition of paintings at Pallant House in Chichester, encapsulates everything I love about Sussex, a landscape I have now crisscrossed on horseback for more than four decades. Chalk Paths, by Eric Ravilious, captures the almost bleak quality of the South Downs in winter, which for centuries was part of the pilgrims’ route to Canterbury. The sense of space and loneliness in Ravilious’s heavily contoured landscape stands in contrast to the area’s heavily populated villages and towns. It reminds me how this place has been home to humankind for millennia, the swelling population eventually pushing back the boar-and-deer-haunted forest of Anderida, leaving the open rolling farmland we see in this picture.

There is an echo, too, of the artist’s war paintings: the scarcity of trees, the barbed wire fences. Ravilious, who spent his childhood in Eastbourne, is perhaps best known for his war work. In the years before he died in an airplane crash in 1942, he created spectacular watercolours, lithographs and drawings of the machinery of war. Perhaps Sussex was on is mind as he did so: the landscape he loved, after all, was all part of what those dreadful machines were fighting for.

This same landscape led me to discover the writers I have shared Sussex with: Rudyard Kipling, Arthur Conan Doyle, EF Benson, Virginia Woolf, WB Yeats, Ezra Pound, Hilaire Belloc, AA Milne, William Cobbett and the Bloomsbury Group. Today the Bloomsbury’s former country retreat, Charleston Farmhouse, is home to an annual literary festival attracting authors from around the world, who speak amid the farmyard scents of hay and silage.

One only has to read these writers to see the effect of Sussex landscapes on them. In The Hound of the Baskervilles, the gloomy, fog-shrouded moors that Arthur Conan Doyle describes are pure Ashdown Forest in winter. WB Yeats wrote that, during the first world war, the longer he and Ezra Pound stayed in Stone Cottage, on the edge of the forest, the harder they found returning to the hubbub of London. Despite its title, Yeats’s famous poem The Lake Isle of Innisfree could easily be about that green haven.

“The focus of this exhibition,” says Simon Martin, director of Pallant House, “is what particular things made Sussex different from elsewhere, those primal elements: the chalk that forms the South Downs and the iconic coastline and cliffs, the rivers and waterways running to the coast, and the woodlands of the weald.”

It is remarkable how many artists and writers have sought and found sanctuary in what Martin describes – escaping the horrors of the first world war, nazism in the second and, in my case, apartheid-era South Africa. Many expatriates have found an echo of their homeland here, from Russian taxi-drivers to Lithuanian and German émigrés, not to mention the many who moved out of London to the countryside. As I ride Sussex now, my horse and I move through two landscapes: the physical one and an enriching one lovingly captured in paint.

Over the years, I’ve heard talk of magic hereabouts: ley lines on the forest, white magic, witchcraft and the fact that this area seems to be a haven for alternative lifestyles and religions. Within a 10-mile radius of my home, there are communities of Rosicrucians, Mormons, Catholic monasteries and retreats, Opus Dei and druids. I don’t pay much heed to any of this, but it is hard to spend any time out in the deepest reaches of Ashdown Forest and not connect with something primordial as well as spiritual.

Sussex is one of the most heavily wooded counties in England and has its own vernacular architecture. The homegrown oak, flint and tile construction that nestles among this landscape of cattle, sheep and grain farming is breathtakingly captured by Ivon Hitchens in Curved Barn, another stunning painting in this exhibition. It is almost as if the barn is itself entangled in the wood, in a setting where elves and witches would fit right in. The Sussex building style shown here – so different from the thatched, whitewashed, gabled and green-shuttered Cape Dutch farmhouses of my childhood – has become part of my adult culture, part of what makes me feel so at home here.

Simon Roberts’ romantic image of a picnicking couple on the South Downs, almost folded into the embracing landscape, is titled We English 13, Devil’s Dyke, yet it could not look less devilish – although cyclists on the annual London to Brighton race might disagree, as the climb is a killer, just 10 miles from a pint after finishing. The painting reminds me of rides I’ve had here chased by russet red Sussex calves hell bent on catching my horse – and the trick of getting through the gate before them.

Sussex is much like a beach, a place caught between the sea and the land. The majority of it lies between two giant 900ft land-waves, the South Downs behind Eastbourne, Brighton and Chichester, and the North Downs, sheltering the county from London’s creeping presence. The trouble with the Downs is that the ridges offer no place to hide from the weather in winter. Walkers and riders are exposed and so Jan and I settled in Ashdown Forest, where the deep valleys and dense woodland offer shelter from the wind and rain.

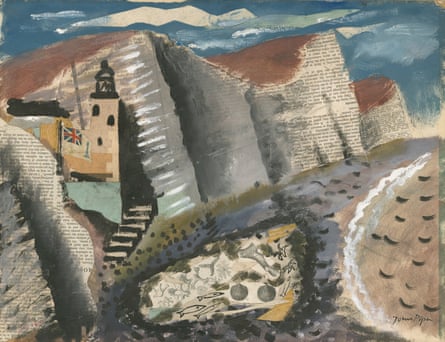

The coast features strongly in the exhibition. I have at times cast a line from Newhaven’s east pier for mackerel in the spring and summer, going home mostly empty-handed but wind burnt and thrilled from seeing France on the horizon. John Piper’s Beach and Star Fish, Seven Sisters Cliff, Eastbourne, brings back the feeling of a fishing rod in my hand and the pull of the tide, his abstracted chalk cliffs creating an almost other-worldly feeling of something beyond us. No less atmospheric is Constable’s Brighton Beach, an essay in loneliness before a stormy sea, an experience those of us who have walked or ridden round these parts know well.

There is a clearing in Ashdown Forest, that I think of as my “church”. As Callum and I enter this intimate tree-columned space, I think how few churches would actually welcome a horseman clip-clopping up the nave to the font. There is just the faintest breath of wind high above us in the branched rafters and above that only sky. The forest stands mute once more, holding a horseman and his horse by a power that neither understands, but which draws them back again and again to this magical place.

Before I understood the terms “forest bathing” or the “nature cure”, or the sacredness of landscape ascribed to it by early man, I sensed something of this as I rode through the heathland and the beechwoods that I found in Sussex. Lifting into a slow canter, Callum carries me effortlessly on the paths rising uphill. The beech trees gleam wet with the morning fog and the rain that came in the night, the diffused light now making each tree its own drama, each a separate figure in this landscape. I breathe deep, taking in this forest offering, this beautiful, satisfying place.

More Stories

An unusual Salvador Dalí painting at the Art Institute of Chicago prompts a startling revelation

Wolfgang and Helene Beltracchi fooled the art market — and made millions

Commuters Go Wild in Matthew Grabelsky’s Uncanny Subway Paintings — Colossal