If you believe of the canonical paintings of little ones in western artwork, their subjects are overwhelmingly white, cherubic newborn Jesuses or aristocratic offspring overdressed in finery to replicate their parents’ standing. Which is a person cause why British artist Matthew Krishanu’s sparse, dreamlike paintings of younger brown boys roaming free and acquiring adventures in subtropical climes – loosely based on himself and his brother as children – come to feel so fresh and persuasive. “The determination even to stand for these figures,” Krishanu claims in his London studio, “and have them on the partitions of galleries about the world, is a response to the historical disempowerment of the brown figure, and of little ones, inside western artwork.”

Childhood and the histories of empire are central themes for the artist, who was born in Bradford to an Indian mother and white British father and lived from the ages of one to 12 in Dhaka, Bangladesh, where his mom and dad labored as missionaries. These encounters have been distilled into ethereal vistas of the brothers boating, exploring landscapes of dashing water and purple mountains, as effectively as inside scenes of missionary exercise in Dhaka.

His forthcoming exhibition Playground, at Niru Ratnam gallery in London, extends the topic of childhood in just an city ecosystem. Paintings of little ones on a climbing frame, balancing on a wall or standing on a veranda line his studio walls, beckoning the viewer into their out-of-time universe like alluring reminiscences one particular cannot very area.

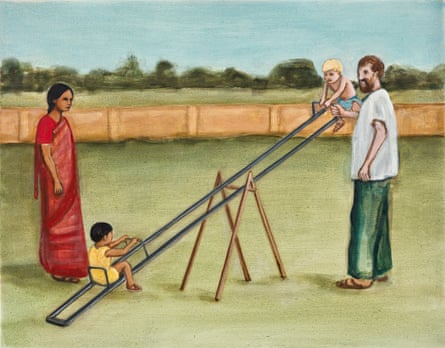

At the show’s main is the titular canvas Playground, from 2020, depicting a brown and a white kid on a seesaw, supervised by a standing female in a sari on one side and a white man on the other. It may be a portrait of childhood innocence, but the positioning of the white kid in the ascendant more than the brown just one is disquieting, evoking the violent heritage of imperial powers making use of Asia as their perform arena.

These undercurrents are subtle nevertheless implicit: Krishanu steers crystal clear of didacticism, far more intrigued in conjuring lived encounters and sensations in his atmospheric work. Figures are fluidly captured, with economic climate of element. “I want the faces to be open up sufficient to be many diverse people’s little ones, as opposed to the absolute particular,” he claims. Specificities of locale and time have been pared back again, imbuing the paintings with what he phone calls “presentness”.

Krishanu builds his worlds from numerous resources. “For me,” he points out, “it’s about setting up a thing somewhere among creativeness, art record, and then perhaps a supply substance, like a photo.” One wall of his studio is taped with printouts of visuals from his intensive archive, testament to his continuing dialogue with artwork historical past. They presently include things like an Egyptian Fayum mummy portrait, a fragment from the Ajanta cave paintings in India, Gainsborough’s The Blue Boy, Rembrandt’s The Polish Rider and an El Greco Christ on the cross.

The artist details to two paintings of four boys and 4 ladies by Edvard Munch that fed into his recent operate Four Little ones (Verandah, 2022), but he has complicated the group’s dynamic by reconfiguring it as two European girls and two brown boys. In all his canvases, the little ones are handled with gravity, not sentimentalised. “There’s a certain variety of authenticity to their participate in that I want to portray,” he states. “The kids have an inside existence and a electricity.” In Boy on a Climbing Body, the issue stands tall, anchored only by the curving frame, sporting a self-possessed, earnest expression as he appears down at the viewer.

In distinction, the older people exude a selected awkwardness, in particular the white foreigners, this kind of as the man in Playground sporting a eco-friendly lungi. “In a way,” claims Krishanu, “any white man or woman in India or Bangladesh is quickly enjoying something of the function of the foreigner or the European, however they position by themselves.” This notion of adults doing culturally built roles is even much more pronounced in the latest sequence Mission, in which his own father is portrayed as the outsider, theatrically dressed in clerical robes, preaching to a Bengali congregation.

With attribute understatedness, the Mission paintings convey Krishanu’s ambivalence about Christianity, particularly the way it has been hijacked by European powers as a device of imperialism and represented in western art. “The point I actually internalised was the depiction of European figures in the Bible,” he states, recalling the leaflets of blond, blue-eyed children and western depictions of the disciples supplied out to Bangladeshi youngsters at a communion services. “Art background has constructed so much of our collective unconscious,” he adds.

Thoughts about race, record and religion underpin Krishanu’s follow but finally what helps make his paintings so beguiling is their ambience of childlike wonder. By juxtaposing real factors, this sort of as climbing frames and seesaws with expanses of gossamer-like pastel washes, he infuses his canvases with an elusive otherworldliness. We discuss the identical entice of Narnia and the “lovely numinous pagan heartbeat” of CS Lewis’s Chronicles, a staple of Krishanu’s childhood. “The numinous and the landscape,” he states, “are pretty a lot about transporting the viewer, though also becoming anchored in the natural and organic qualities of the paint – what a drip is, what a clear veil of paint about white is. Which is the great duality of a portray.”

More Stories

An unusual Salvador Dalí painting at the Art Institute of Chicago prompts a startling revelation

Wolfgang and Helene Beltracchi fooled the art market — and made millions

Commuters Go Wild in Matthew Grabelsky’s Uncanny Subway Paintings — Colossal